The Revolution Was Televised: "Form" and "Meaning" in the Islamic Republic

- yuvalkh

- Jan 2

- 19 min read

Updated: Feb 9

Author: Yuval Klein

The dichotomy between “form” and “meaning” will be explored in its multiple resonances – social and religious, Iranian and universal – each of which inform one another. It will first be applied to Sufism by way of the film Baran (2001), which I have analyzed exhaustively. In the vein of ghazal (Sufi love poetry), the protagonist of Baran undergoes an inward transformation in which the sublunary “form” (sura) is negated in the pursuit of a divine, noumenal “meaning” (ma’na). Mystical undertones texture the film’s social realist character, from which a secular reading of form and meaning can and will be derived. Then, I will write about how propaganda during the Iran-Iraq war effectively transformed the formlessness of death into a collectively imagined meaning. This process is consistent with the classical ghazal arc that is incorporated into Baran, of radically negating form. I proceed to discuss the destabilizing effect of the subcultural, particularly when it is represented publicly. This relates to Bahram Beyzaie’s Bashu, the Little Stranger (1989), in which the form of the state is subordinated to the meaning of lived experience. Both Baran and Bashu embody “matter out of place,” pollutants that attempt to transform their statuses into one of “matter in place.” The subcultural “matter out of place,” I will argue, is an affront to the normative order both on a micro and macro scale.

In the opening sequence of Baran, a baker’s hands are shown kneading dough. This recalls the first scene of the director Majid Majidi’s earlier film Children of Heaven, in which the camera lingers on a bazaari’s ravaged hands attending to a child’s similarly ravaged shoe with deft and caring strokes. We are thus immersed in a disorientingly diminished window of subjectivity without the panoramic transparency of a spacious “establishing shot.” Baran’s opening sequence is in dialogue with humanity's origin story in the Quran, in which God makes man out of clay. There is a higher entity at play that is puppeteering the symbolic dough, heralding a fatalistic vision of nature; or, conversely, a human hand is being shown exerting agency over fate, albeit on an infinitesimal scale. The protagonist, Lateef, is then shown buying bread.

Lateef leaves the bread shop, observes a young couple playing a makeshift game with a hat and then smiles as one of them declares that she has won. He stops beside a window pane and adjusts his hair, utterly rapt by his own reflection. Claiming victory over another and observing one’s own reflection are vain demonstrations of the nafs, which is the primal and satanic ego; the obverse is the ruh (spirit), which can have knowledge of itself and be known by God, but the nafs is chronically oblivious to it (Rumi-Chittick, 1983, 12). After walking a few paces, Lateef eyes a coin on the ground and illicitly conceals it with the sole of his shoe before pocketing it. This parallels the final scene in which he rejoices at the sight of his beloved’s footprint. In the coin scene, Lateef is exhibiting venal impulses derived from the nafs, whereas in its later mutation, there is the recognition of divine knowledge derived from the ruh. He looks down at the sublunary stuff of “form,” and later, the transcendental stuff of “meaning.”

In a convenience store, Lateef drops a product from its designated shelf; he picks it up and puts it in its proper place out of propriety. He is doing so mindlessly, bereft of ‘erfan (gnosis). Over the counter, Lateef is given a forged identity card, which represents the nafs throughout the film. By attributing meaning to this object, he is deriving a sense of self from an erroneous source. The store clerk who sells Lateef the card asks for his name; Lateef mocks the fact that he never remembers it, as though this habit of his is comically incorrigible… in fact, it is. Lateef, which means “kind” or “gentle” in Arabic, is one of God’s 99 names in the Quran; it is, therefore, not only the name that eludes the store clerk, but also the veiled ruh that it describes. He will never recognize Lateef.

A close-up of the clerk’s hands writing a receipt recalls the opening scene in which a baker is kneading dough – again, whether this manual act of creation represents man’s agency or a fatalistic negation remains delightfully enigmatic. In this transaction, the nafs is being foisted upon Lateef by a person to whom his ruh is incomprehensible. The scenery shifts to a construction site in which an elderly Afghan worker has been injured. Our protagonist – with his youthful and tattered appearance – is soon revealed to be a chai wallah for the laborers there. He is shown tossing a sugar cube into the air, failing to meet it with his mouth receptively agape, and then, bending down, thereby demeaning himself in order to retrieve it; not unlike the scene in which he picks up a fallen coin, he is a pathetic gleaner of petty riches.

So as not to reduce Baran to an exhaustive, rarefied philosophical allegory, I will describe the film in its capacity as a work of social realism. Lateef’s boss Memar is withholding his salary and those of his peers, such that they are bound to evidently harsh working conditions, unable to abandon a hibernating salary. In their shared neglect, the Iranian and Afghan workers are pitted against each other; two frustrated Iranian workers voice indignation towards Memar at the fact that employment of migrant Afghan workers, who are not legally permitted to fill these occupational vacancies, is eroding at their de jure wages, or are at least being used as a pretense to that effect. Lateef also tries to wrest money from the boss to no avail.

Baran, who comes to represent the Divine, wades through the site alongside a relative named Soltan. She disguises her gender in order to become a veritable replacement for her father – the previously mentioned injured Afghan who is unable to work in lieu of his health – in Memar's eyes. Soltan implores him to hire Baran in spite of her perceived physical weakness. While Memar is scrutinizing Baran, there are a series of obstructions to her more inward qualities: clothes, deceit, silence, and a smoke that gathers about her face. In the latter case, the “form” of smoke is concealing her face, and he can only penetrate to the formless “meaning,” i.e. her divinity, by negating form. The clothes hide the non-mystical “meaning” of her femininity, and perhaps, morbid beauty. In Sufi love poetry (ghazal), poems address a female and godly beloved interchangeably (Rumi-Chittick, 1983, 286). There is, therefore, a rich dialectic between the secular and religious imagery, one that is very much present in this contemporary ghazal film. In the face of deceit, Memar is inclined to misunderstand her “meaning.” His uncritical reception of lies further widens the epistemic gap to that elusive and allusive Baran. The elision of her voice, which largely continues throughout the film, lends immensely to both a mystical and political reading.

One function of silence throughout the film is to represent the Afghans’ marginalization. In multiple instances, the Iranian characters are raucous, whereas their Afghan counterparts are shrouded with a veil of silence. This aural dimension is consistent with a visual one, whereby Afghan laborers are systematically concealed from the authorities, and in the film, they reside in a sequestered enclave that is only reachable by way of a concealed physical and spiritual path. Silence is relished in Sufism to a similar effect as Wittgenstein’s oft-quoted “whereof one does not know, thereof one must be silent.” It is shameful to speak words in the absence of meaning. In Lateef’s trajectory, silence gradually descends upon him, and from the void it creates, the apex of ‘erfan – that is, haqiqa – juts its head. Baran is silent because God does not speak – also, because the imagery of Baran is a language unto itself. Finally, she is only important insofar as she elicits certain profundities in our protagonist. Lateef is the arbiter of his love for her, the bard who conceives of his beloved. He is the voice.

Baran, who adopts the name Rahmat, proves too dainty to endure the harsh manual labor. Instead, she assumes Lateef’s facile chores, condemning him to the same grueling physical exertion as the other workers. Lateef sits adjacent to Baran, petulantly throwing rocks at pigeons and then a metal column. In a later scene, soon after falling in love, he witnesses Baran tenderly feeding the pigeons. This moves him, such that after she leaves the site alongside his other hapless migrant peers, he emulates her. Interrupting his rock-slinging, Memar orders Lateef to show Baran the ropes, so to speak, of his job. He refuses to lead by example, and instead, lashes out on her. To Lateef’s dissatisfaction, her tea is widely celebrated by the workers. When she offers him a cup, he grabs and immediately empties it on the tray. In doing so, Lateef scorns an opportunity for respite and prolongs his solitary frustration. At the height of disgruntlement, he plunders Baran’s domain, a small room in which she prepares the meals and tea plates behind a separating curtain. In the aftermath, she refurbishes the room with unwavering resolve.

His pettiness persists for a bit longer, dissipating with a long-winded experience of revelation. In the preceding moments, a wind momentarily incapacitates him, compelling him to cast away the sack resting on his arms. Furthermore, the curtain to Baran’s room is enticingly lifted. Past the rustling curtains, a reflection can be vaguely made out. At this point, it is worth noting that, in Arabic, ruh can connote either ‘spirit’ or ‘wind.’ The ruh is, therefore, asserting itself through God’s intercession. He observes her muddled reflection, lifting two physical veils: the curtain and the headscarf.

The lovestruck Lateef attempts to run down the stairs of the site in order to greet “Rahmat,” but Memar blocks him, insting that “there is a wall to knock down.” Essentially, Lateef has more work to do before union with the divine. There are, in fact, more barriers at the moment; the wall is a Memar that curbs his advances as well as an unbanished nafs. Through the perforated wall, a shaft of light seeps through. As in Plato’s cave, light is likened to knowledge. In the next shot, a close-up of fire and water are shown in succession. These two elements cancel one another, allowing them to stand for a variety of other binaries in Sufism (Rumi-Chittick, 1983, 52).

In a feat of heroism, Lateef disentangles Baran from the clutches of a police officer and receives a beating. Upon learning about the Afghan presence, the authorities cleansed the site of all migrant workers. Separated thereafter, Lateef finds an isolated forest with a paved path and traverses it in pursuit of his beloved. There, he finds a place in which many Afghans have convened. He is handed a warm cup of milk, and in drinking it, experiences a sort of renewal. Lateef then finds Baran toiling away as a boulder-pusher and is disconcerted by the physical torment that he watches her endure. He once again attempts to coax Memar into releasing his salary, this time channeling his passion for Baran in eliciting pity. Memar relents, and Lateef triumphantly reallocates the funds to Baran’s household by way of Soltan, that is, until Najaf gives all of it back to Soltan in order to smuggle his friend back into Afghanistan. Lateef becomes increasingly immersed in Baran and her family’s hardships, meeting the sight of privation with rheumy eyes and acting upon their perceived needs. At the culmination, he sells his identity card and transfers the profit to Najaf under the false pretense that it is from Memar. Memar simply hoarded Najaf’s hard-earned salary indefinitely without repercussions. In tearing the photograph from his card, Lateef has jettisoned the nafs.

The film concludes with Baran and her family’s departure to Afghanistan. Baran fumbles her groceries and Lateef helps her, relishing the act of serving his beloved. For the first time, she reveals her face in its entirety, but she swiftly covers it with a perforated burka. In Islam, there is a general tendency to scorn mimetic representations of the prophet Muhammad, and, of course, God, out of fear that they will be worshipped as idols. There is also a trope in ghazal of the beloved’s beauty being so overwhelming that it cannot be glimpsed directly. As the car evanesces, a flock of birds circle overhead. Perhaps they are refugees, or, like in Conference of the Birds, Sufis seeking an elusive source of emanation; perhaps, they, too, are on a proverbial “path” to the divine. Once Lateef is left alone, he notices his beloved’s footprint, soon to be awash by rain. Her form is thus washed away, with only a noumenal “meaning” lingering on.

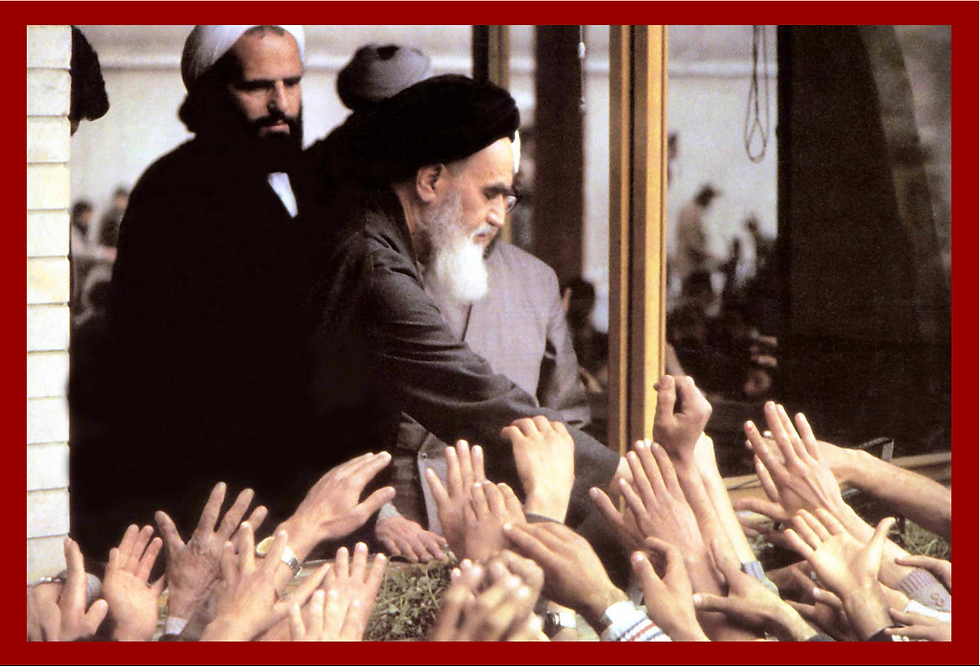

The Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), which lasted eight years and claimed more than one million lives, was perpetuated in tandem – though asymmetrically – by a psychopath (Saddam Hussein) and a zealot (Ayatollah Khomeini). In Khomeini’s Iran, propaganda played an important role in mobilizing citizens to serve his existential – vaguely messianic – war, the most important Shi’ite one since Husayn’s infamous defeat in Karbala (Anzali, 2017, 5). A cult of martyrdom was conceptualized through eclectic sources, drawing upon mystical love poetry and an ingrained Shi’ite persecution narrative. Journeying into the battlefield, soldiers were supposedly traversing a mystical path in pursuit of their immaterial beloved (Seyed-Gohrab, 2012, 267). The martyr – a soldier of love – is able to transcend mortality by achieving a saintly status, encountering God, and then returning as a source of emanation, one who leads his people on earth through civic example (Seyed-Gohrab, 261).

The Ba’athist forces invaded Khuzestan in September of 1980, soon after Saddam publically shredded the Algiers Declaration of 1975, which partitioned the Shatt al-Arab waterway between Iran and Iraq (Amanat, 2017, 830). The nascent Islamic Republic’s fraught legitimacy in lieu of the ongoing hostage crisis, as well as a sizable Arabic-speaking minority in Khuzestan, provided an opportunity to satiate Saddam’s expansionist ambitions. His planned-for quick victory seemed imminent after a few weeks of significant Ba’athist advances. However, a miraculous effort on the part of the Revolutionary Guard, a truncated Armed Forces, and later, too, the inordinately young and inexperienced Basij volunteer militia, dramatically shifted the momentum, such that after a year of fighting, the Iraqi invaders were unequivocally ousted (Amanat, 2017, 832).

Iran proceeded to launch a long-winded offensive that would resolve itself in a stalemate after nearly eight years of fatal trench warfare (Amanat, 2017, 834). But how was fatality “transformed” into meaning? In the formlessness of death and subsistence, a meaning was derived. The convenient Baran analogy is in no way fortuitous, rather, the war volunteers and Lateef belong to the same love-crazed cult of martyrdom. Martyrs were accumulating national symbols, instrumentalized in, as Benedicts Anderson writes, “transforming fatality to continuity… contingency into meaning.” The ability to do so has determined the longevity of the most resilient religions, as well as secular nationalism (Anderson, 1983, 11). Mass graves are void of any inherent form-derived “meaning.” They are hollow containers in which to pour bountiful imagined meanings. As Anderson writes, “no more arresting emblems of the modern culture of nationalism exist than cenotaphs and tombs of Unknown soldiers" (Anderson, 9). In light of this, one can understand how the pervasive wartime rhetoric promoted by Khomeini stays abreast of other ad hoc war propagandas and reifications of the collective.

An oft-quoted Iran-Iraq war declaration by Khomeini goes, “Our leader is a twelve-year-old who throws himself under the tank with a grenade in hand” (Amanat 2017, 836). He is referring to Muhammad Husayn Fahmida, one of many child soldiers who were sent on suicide missions – called “cannon fodder,” and, even more ominously, “human waves” – that cleared the way for army offensives (Seyed-Gohrab, 261)(Amanat 2017, 836). This reprehensible strategy and its concomitant cost of human life was justified in many ways apart from the classic “vanquishing of an evil pollutant” story. Battles were reputed to be profound experiences of ecstasy about which martyrs wrote last testaments that were widely disseminated through propaganda publications (Amanat 2017, 838). Rather than victory, the goal was a longed for union with the immaterial beloved. Asghar Seyed-Gohrab poignantly notes that this mystical militancy, so to speak, repurposed innocuous, and, of course, unparalleled metaphors of love, and transformed them by way of transferring them into reality. After all, when referring to ecstasy, “such [phrases] as ‘dancing without head and feet,’ when transferred to the battlefield, are not merely metaphoric" (Seyed-Gohrab, 259-60).

In political discourse and quotidian exchange alike, people think and speak metonymically – that is, concepts are understood in terms of another. Regardless, the extent to which a harrowing battle, tormented love, and ascetic religious devotion were likened to one another during the Iran-Iraq war is remarkable. The seamless metonymic flourish in ghazal and wartime propaganda benefit from a dearth of gender distinctions in the Persian language. On the amenable linguistic canvas of Persian, a rich canon of medieval love poetry was invoked, in which mystics wrote about that same distant and bloodthirsty beloved who leaves the lover martyred (Seyed-Gohrab, 251). Its form, content, and imagery were used to perpetuate a senseless war, eclipsing its character with the illusion of continuity.

Sufism in the Islamic Republic, though imprinted in mainstream clerical theology, is largely marginalized in Iranian society. Clerical proponents of mysticism remain at the fringe of the seminary hierocracy, enduring marginalization, and at times, outright persecution for their beliefs (Anzali, 3). One of those eccentrics was Khomeini, whose mystical inclination was so radical that, even after the revolution, some of his broadcasted lectures were censored due to outcry from clerics over their esoteric Quranic commentary (Anzali, 4). Though unsympathetic to institutional forms of mysticism, organized Sufism continued uninterrupted during Khomeini’s reign. It was tolerated in its private form, but the establishment had little patience for ostentatious displays of its existence. Of course, this is absurd in lieu of such profligate and public instrumentalization of precisely that tradition in service of the wartime subterfuge. Also, during the revolution, Sufi mourning rituals were repurposed to protest the Shah on a massive scale (Bos 2002). The origin of the clergy’s hypocrisy is, once again, rhetorical. The now widely tolerated school of ‘erfan gradually found legitimacy in the mainstream and is increasingly taught in the seminaries (Anzali, 6). In allowing a selectively revised mysticism to be subsumed into the mainstream, its traditional predecessor loses relevance. Sufism, in effect, is superseded and rendered obsolete.

In contrast to his predecessor, Ayatollah Khamenei was disinterested and intolerant of Sufism. However, the reformist atmosphere of the Rafsanjani and Khatami years inhibited his wrath, such that an influx of persecution only surfaced during Mahmud Ahmadinejad’s subsequent presidency. In his capacity as regime hardliner, Ahmadinejad’s primary role was raising the pulpit of the clerical establishment. Sufi disdain for “guardianship of the jurists” essentially usurps all spiritual authority from the clergy and transfers it to a spiritual master, to whom an ascetic must yield all loyalty. At a time in which power was unprecedentedly centralized, spheres in which to negotiate autonomy were compromised. In May of 2006, Niʿmatullahi dervishes clashed with the revolutionary guards after one of their most important centers was plundered. Sufi institutions have since been increasingly harassed (Anzali, 7). Formerly, the “meaning” of their beliefs was tolerated as long as a veil of conceit (form) was present, then one party ceased to acknowledge this posturing.

In immediate post-war Iran, the The Islamic Propagation Council published a pamphlet on martyrdom by a war volunteer and university student entitled ‘Red Mysticism,’ which declares that the laudable energy stirred up from mystical martyrdom during the war must henceforth be channelled into mundane moral acts (Bos, 175-7). This seamless shift from Lesser to Greater Jihad illustrates the ingrained dialectic between two differentiated registers of existence in the context of the Islamic Republic. The proclamation in ‘Red mysticism’ heralds a shift from an era that necessitated indulgence of “form” in favor of the nation’s longevity to a collective repatriation into “meaning.” In Bashu, the camera lingers on the greater stuff of “meaning,” which compels one to depart with the overarching “form” of the state. Unfortunately for Beyzaie, this shift was being heralded prematurely in the eyes of his censors. In lieu of their varnishing contention, Bashu carried a prescient, rather than ill-timed statement; it offers, in retrospect, a latent and haunting clarity at a time in which Khomeini’s messianic vision fatefully reigned.

In Bashu, the Little Stranger (1989), an internally displaced Iran-Iraq War refugee – an Arabic-speaking child from Khuzestan with East African heritage – finds himself in a strange, distant village in the Northern Iranian province of Gilak. The protagonist’s trajectory is similar to that of Baran, as both are displaced into dissonant corners of Iran and must accordingly negotiate spheres of belonging within them. Both attempt to transform their statuses from “pollution” to partial acceptance. Also, neither Bashu nor Baran immediately reveal certain aspects of their identity outwardly, instead, wearing a veil of silence. As in some of Beyzaie’s notable earlier works – e.g. Downpour (1972) and Stranger and the Fog (1974) – the protagonist is removed from his milieu and finds himself elsewhere, surrounded by people to whom he is a stranger. The imposition of a foreigner – an anomaly – disrupts the normative order of the insular Gilaki community. Bashu must turn his status from one of “matter out of place” to one of “matter in place.” During the Iran-Iraq War, complicating a pretext of social cohesion was particularly transgressive.

A total war necessitates mass mobilization that precludes the infirmities of a fragmented national unit. Any depiction of disunity becomes, in effect, blasphemous. Throughout much of the film, the contrast in the characters’ appearances and linguistic backgrounds is so vast that neither one of them can conceptualize the other within their own reductive, monolithic molds of Iranian-ness. They must come to recognize the “Self” in the “Other.” Portrayal of an Iran whose citizens have such disparate, distant, and dissimilar experiences complicates a narrowly regimented conception of Iranian statehood, one of a collectively oppressed people – of oneness.

When confronted with an anomalous agent of a held national identity, one must adjust one’s national posturing. Both Bashu and the villagers saw an anomaly in one another – and the anomaly has an uncanny ability to pollute cognitive categories. After close scrutiny, it may deprive them of their legitimacy. As Mary Douglas writes, “Dirt is matter out of place” (Douglas, 1966). Bashu’s presence in this village can be understood in those terms. So, how does one address dirt? There are a few answers: 1. Clean it/rinse it: Nai’i, in fact, ventures to rinse him, an act that fails to produce the desired effect of brightening his pigment. 2. Get rid of it: Many of the villagers advocate for this, but alas, he stays put. 3. Assimilate one’s notions of what is pure to encapsulate the object in question, thereby inverting its status to one of “matter in place.” At the end, the villagers broadened their notion of family and community, embracing Bashu as a person whose presence is consistent with their acquired understanding of family and national identity.

The “purity” vs. “pollution” paradigm is at the core of Iran’s foundational religions of Zoroastrianism and Shi’ism. Long before the age of “imagined communities,” the Iranian identity was extant. The land of Iran – a rather fluid domain not corresponding with the modern and problematically crystallized borders – in effect, constituted a sacred space that was to be protected from non-Iranians. This endemic notion of inviolable borders naturally permeates into a repetitive and adaptive rhetoric of nativism, whereby perceived pollutants resurface in each distillation of Iranian national reiteration (Amanat 2012). Baha'is, for example, have been arbitrarily branded “matter out of place” in post-revolutionary Iran. Afghans are condemned to a similar status in popular discourse. Outside of Iran, analogs can be found in the great replacement theory, the precociously racist language of “limpieza de sangre” (purity of blood) in pre-Spain Iberia, and the Hindu caste system, all of which testify to the paradigm’s timelessness and universality. In fact, Mary Douglas’ seminal commentaries upon such phenomena were done with the stated purpose of likening practices of “modernity” to those of the traditional arcane subjects of anthropology; in the latter, superstitious separation of pollutants and ritual defilement are more evident, and are, in effect, disproportionately emphasized in her discipline.

Nina Khamsy notes that during the Iran-Iraq war, the Iranian nation was conceptualized as a female geo-body in need of protection from Arab penetration. I argue that Beyzaie treats Bashu, rather than his motherland, as the primary object of purity – that war, as well as ethnic intolerance, are the pollutants that must be dispelled. As Khamsy notes, Bashu is pre-socialized, thus uncorrupted (Khamsy 2024). Nai’i is a mother who protects Bashu when the state doesn’t. She is a state unto herself, one with hegemony over its children – meet the seductive gaze of an admirable para-establishment vanguard, whose nonconformist vision ultimately prevails. It is no surprise, then, that Iranian authorities were particularly intimidated by one scene (a mesmerizing one) in which Nai’i gazes directly at the camera. For a woman – or rather, an agential single mother in a peripheral non-Persian-speaking Iranian province – to meet the eyes of so many Iranians erred criminally into the transgressive.

In the first gathering of the community, everyone advocates for Bashu’s immediate dispossession. The second gathering parallels the first; Bashu is gone, and the overall regard for his life is suddenly and sentimentally lifted to great heights. Likewise, boys were herded to the battlefield, becoming subsequently martyred in the eyes of their peers. Like the villagers, many ostentatiously showcased their remorse for the deceased young soldier, even while glorifying the perpetuation of what was, at this stage of the war, pointless carnage. With an ideology in which dead children arouse pride while the domesticated ones are belittled, there arises a perverse system of valuing human life.

Whereas the film argues that children need mothering, the regime thinks they need glory and dispossession. At one point, Nai’i says that Bashu is “the son of the sun and the earth,” i.e. should belong to the worldly as opposed to the other-worldliness of death. Bashu helps Nai’i write a note to her husband that explains why Bashu is important to her as a person and asset. Surreally, a platoon of soldiers can be vaguely made out, standing inert in the background. Though written for a specific person, it addresses a larger audience. She is a mother explaining why it isn’t shameful that her son lives with her. The child’s place is alongside his mother, not in a perilous exile. Finally, there was a medicine man who didn't tend to, nor even care, for his patients’ livelihood. Just like Khomeini’s regime, the medicine man is a powerful entity that meets human suffering with callous indifference. Also, the medicine is sympathetic to all demographics of Iran. Therefore, just as the medicine belongs to both Nai’i and Bashu, so too, the auspices of Iranian protection. The need for medicine reflects the need for healing after a long and grueling war, a need that was repeatedly neglected.

In the end of the film, an “awakening” of Iranian-ness allows the characters to mobilize in curbing that invasive and allusive boar. In Beyzaie’s vision of linguistic and cultural cohesion in Iran, the characters reconcile their differences amongst themselves before any mention of an outsider is introduced. Only in the conclusion, after the characters have reconciled their differences, do they have a notion of themselves vis-à-vis an enemy. Most of the film is focused on the meaning of Iranian lived experience, but it then shifts to a portrayal of form, culminating in the ultimate stratification of nature into one of heterogeneous Iranians, a flock of birds, and an allusive vermin/pollutant. In lieu of this conclusion, does the film ultimately resort to a militant, or even conformist, commentary on the war? In a vacuum, one would rightly note that the “form” is conducive to this interpretation. However, the scene’s “meaning” is transformed by the overarching details – the subversive centering of femininity and motherhood, wresting of linguistic and ethnic divides from the margins of what Michael Herzfeld calls “cultural intimacy” (the embarrassing characteristics of a nation that are strategically muted in its external expression of identity, and forging an unglorified mimetic artwork (Herzfeld 1996). The image of Iranians mobilized against a common enemy is notably absent throughout most of the film. Instead, audiences are condemned to the abject reality of a child in a state of suffering and neglect, whose condition gradually improves upon meeting his adopted mother. The external front of the Iranian nation is, in effect, subordinated to the lived experiences of sub-Persianate Iranian minorities.

Bibliography

Amanat, Abbas. “Facing the Foe: The Hostage Crisis, the Iraq-Iran War, and the Aftermath (1979–1989).” In Iran : A Modern History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

———. “Introduction: Iranian Identity Boundaries A Historical Overview.” In Iran Facing Others, edited by Abbas Amanat and Farzin Vejdani, 1–33. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137013408_1.

———. Iran : A Modern History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities : Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev. ed. London: Verso, 1991.

Anzali, Ata. “Mysticism” in Iran: The Safavid Roots of a Modern Concept. 1st ed. University of South Carolina Press: Columbia, South Carolina, 2017.

———. “Introduction: The Question of ʿIrfan in Contemporary Iran.” In “Mysticism” in Iran The Safavid Roots of a Modern Concept, 1st ed. University of South Carolina Press: Columbia, South Carolina, 2017.

Bos, Matthijs van den. Mystic Regimes : Sufism and the State in Iran, from the Late Qajar Era to the Islamic Republic. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1969.

Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī. The Sufi Path of Love :The Spiritual Teachings of Rumi. Translated by William C Chittick. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983.

Herzfeld, Michael. Cultural Intimacy : Social Poetics and the Real Life of States, Societies, and Institutions. New York & London: Routledge, 2016.

Khamsy, Nina. “Little Strangers: Representations of Displaced Youth in Iranian New Wave Cinema.” In The Plays and Films of Bahram Beyzaie : Origins, Forms and Functions, edited by Saeed Talajooy. London: I.B Tauris, 2024.

Seyed-Gohrab, Asghar. “Martyrdom as Piety: Mysticism and National Identity in Iran-Iraq War Poetry,” Der Islam, 87, no. 1–2 (2012): 248–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/islam-2011-0031.

Talajooy, Saeed and Bloomsbury (Firm). The Plays and Films of Bahram Beyzaie : Origins, Forms and Functions. London: I.B Tauris, 2024.

Comments